In 2011, through the NoAcademy research program on social design, I came in contact with a big social housing corporation in The Netherlands for a potential contribution to one of their projects; a renewal of the whole entrance of a city by demolishing 162 social housing dwellings and building new ones.

The population of the specific area is very diverse, a typical example of the consequences of the demographic developments of the post-war reconstructions with its low cost blocks.

· On the 6th of October 2011 I presented a proposal at the offices of the social housing corporation for a project related to the specific renewal project and area.

After some agreements and disagreements we settled on making a new appointment to present my proposal remodeled.

In the meanwhile I started contacting some of the inhabitants to find out my self if they really agreed with the plans of the demolition of their houses, although I was informed by the corporation that more than the 70% of them said yes.

That was a number which was needed in order to proceed the renewal project.

· On the 20th of October 2011 I received an e-mail by the social housing corporation telling me that I was going too fast and that asking the people again was not appropriate because the project of demolition of the buildings is political sensitive.

· On the 2nd of November I sent an e-mail to my contact person from the corporation to inform them about the presentation of my research at the W139 gallery in Amsterdam.

The letter below is their reply to my e-mail.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

· RE: presentation of the Apapa-zone research/project

From: Lola (lola@the-alienation.nl)

Sent: Wednesday, November 02, 2011 4:18:42 PM

To: kali nikolou (nikoloukali2004@hotmail.com)

Cc: Alotta, Pool van der (vanderpool@the-alienation.nl); Ziek, Lon van der (vanderziek@the-alienation.nl); roro@forum.nl

Dear Kali,

I think there is a misunderstanding. We don’t have an agreement on this project. In our last meeting we agreed

you would do some research (talk to children and women at Apapa-ki) in order to get ideas for a sculpture or

images that belong to Apapa. In our next meeting you would give a presentation about the new ideas and after

we would decide if we wanted to continue.

Last month you informed me about the results of the interviews that took place in Apapa. I sent you a mail

because I didn’t agree with this method (see attached mail). Now you anounce a public presentation of your

research in an art gallery in A’dam. I don’t like that at all and I can’t agree you are doing this on behalve of The

Alienation.

I’m sorry Kali, but I think we don’t understand each other well enough. Therefore I don’t want to continue in this

project. I also ask you to cancel your public presentation in the art gallery in Amsterdam. And if you still want to

continue the presentation in Amsterdam, please don’t mention our name, names of inhabitants, Apapa or

others names. Maybee you can use fake-names.

Met vriendelijke groet,

Lola

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

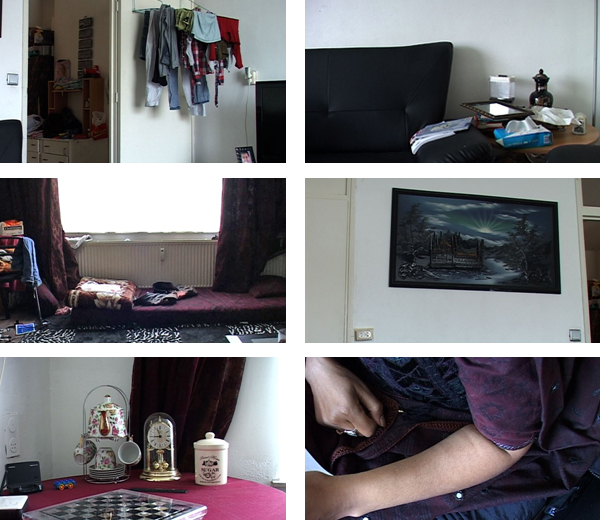

During this whole process I visited one of the inhabitants of the buildings who are going to be demolished.

A very welcoming woman told me her own short story about her house after me asking her about an object I found in her living room, a sugar pot.

video

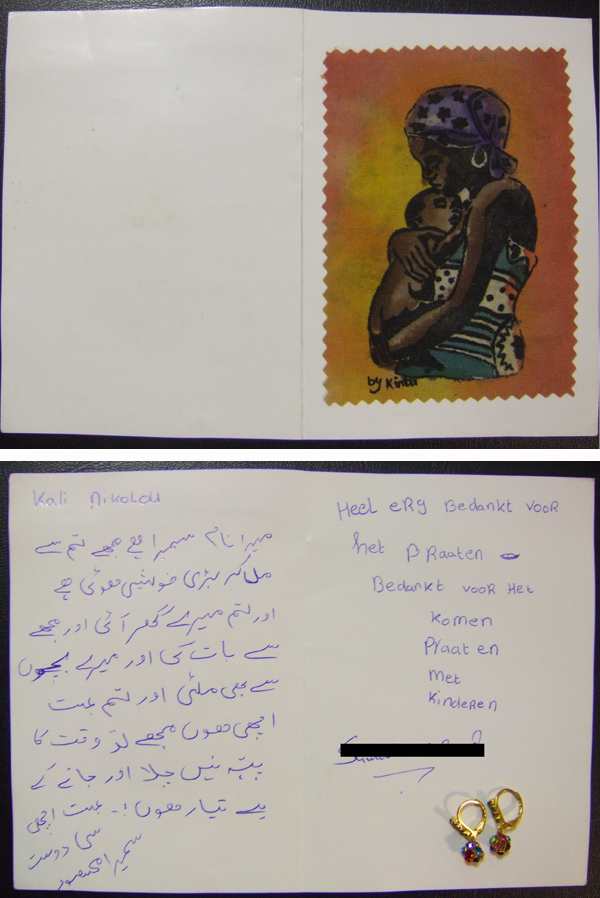

Before I left she gave me a card in which she, in her native language, and her daughter, in Dutch, wrote me how much they enjoyed our conversation. The card was accompanied by a pair of earrings from her country.

We will meet again.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part of my research about social housing in The Netherlands:

In 1901, social housing in The Netherlands was given a solid base with the Housing Act, which made it possible for private organizations with government support to build ‘for the general good’. The peak of the production of social dwellings was between 1916 and 1925. In that period new housing blocks subsidized by the state started to appear which were not only affordable but also very appealing. The Amsterdam’s School was the main architectural style which started a new era related to the social housing status in The Netherlands. This architectural style, recognizable by its unique decorations, was expressing the modern aspirations of its time. It has been interpreted both as a visual translation of the hopes and aspirations of social democratic workers and as an example of the social engagement of the twentieth-century architects.

These architects would have never been able to develop in such a characteristic fashion without the existing peculiar political situation of the time. SDAP, Social Democratic Workers Party, found in 1894 became the biggest socialist party having housing for the workers its main preoccupation.

The Amsteram’s School most important feature was the close ties between political and cultural life.

During the crisis years, between 1933 and 1939, the production of social dwellings got much less. The WWII destroyed many of them. Afterwards a big need was manifested for new constructions where the quality became a minor issue. Furthermore, the new architectural style was characterized by its soberness and functionalism which were more important than its appearance. Planners started to turn increasingly to more and more utopian constructions.

In the 1960s there was a mass production of high-rise buildings in order to reduce the costs. Many areas, mainly suburban, were built in order to construct the modern world. The Bijlmeer Plan, for example, was described to the press in 1965 by the Social Democratic Mayor, Van Hall, as a blueprint for “an area with future value”.

Today there are the neo-liberal politics of welfare state reform which are closely related with discourses of choice and personal responsibility which appeals attractive to the general mass.

The most recent national housing policy memorandum on housing Mensen, Wensen, Wonen was held in 2001 and it is characterized by its neo-liberal tendencies. The memorandum emphasizes greater individual choice on the housing market by reducing the social rental sector through demolition and sales, and by encouraging owner occupancy through new constructions.

In the Netherlands the early providers of social rented housing were predominantly local authorities. Later, non-municipal housing associations started to take over and in the beginning of the 1990s for the first time they were made almost completely independent from the government. Within the new framework these associations became responsible for determining their own asset management policies.

Social housing is an example of public, political and collective architecture. In The Netherlands, which is considered to be the Mecca of Social Housing, these dwellings are being subjected to unprecedented innovations that are drawn from the Dutch process of urbanization and are part of the creation of the national identity.

Social housing is an intervention in markets, which effect social patterns in cities. The housing context is a reflection of politics, ideologies, art, architecture and social service.

By 1989 the policy and political environment created the fertile soil for plans which were developed in order to reduce the percentage of newly built subsidized (rental and owner-occupier) dwellings from about 75 per cent to about 50 per cent in 1997.

In 1998 a regeneration of many neighborhoods in the country was allowed.

A recent example of these neighborhoods is the area I visited for this project.